America’s mortality map reveals a grim truth: what’s most likely to kill you depends heavily on where you live. In a new analysis of national death statistics, researcher Scott Vicknair uncovered critical geographic patterns in how disease, injury, and chronic illness take lives across the United States. The findings highlight that health disparities are shaped as much by environment and access as by personal choices.

Top Killers Vary by State

Nationally, heart disease remains the number one cause of death, responsible for more than 21% of all annual fatalities. Cancer follows closely at 18.5%, while accidental injuries claim over 227,000 lives each year. Yet state-level breakdowns reveal striking variations.

- In the “Stroke Belt”—an 11-state region including Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, and North Carolina—stroke and heart disease mortality rates are significantly elevated. Oklahoma ranks worst for heart-related deaths, with 257.1 deaths per 100,000 people.

- Kentucky, Louisiana, and Arkansas top the list for the highest cancer diagnosis rates, while Montana and Wyoming experience disproportionately high accidental death rates due to hazardous labor conditions and limited emergency medical access.

Environmental and Industry-Driven Risk Factors

Regional industries and environmental conditions also shape mortality outcomes. Coal-mining areas like West Virginia report higher rates of chronic respiratory disease, likely tied to long-term exposure to particulate matter.

In New Mexico and Arizona, dry climates and higher rates of alcohol consumption contribute to the nation’s highest chronic liver disease deaths. Meanwhile, Florida’s large elderly population sees Alzheimer’s disease claim more lives than in most other states.

These variations underscore how local economies, demographics, and environments drive health risks that extend beyond individual lifestyle choices.

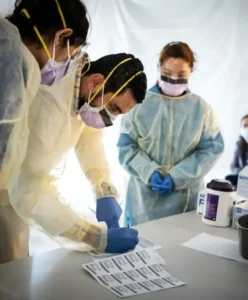

How COVID-19 Shifted the Landscape

COVID-19 has become the fourth leading cause of death nationwide, responsible for 5.7% of all fatalities. The pandemic’s toll was not distributed equally: states with low vaccination rates and limited healthcare infrastructure reported significantly higher death rates.

Vicknair’s data also shows disproportionate impacts on Hispanic and Black communities. For every white American lost to COVID-19, 1.6 Hispanic individuals died from the virus, reflecting longstanding disparities in access and outcomes.

State Rankings by Cause of Death

Some of the starkest patterns include:

- Top Heart Disease Death Rates: Oklahoma, Mississippi, Alabama

- Highest Cancer Rates: Kentucky (503.4 per 100,000), Louisiana, Arkansas

- Most Accidental Deaths: Wyoming, Montana

- Chronic Respiratory Disease Hotspot: West Virginia

- Liver Disease Leaders: New Mexico, Arizona

- Alzheimer’s Prevalence: Florida

These findings reflect not only medical conditions but also social and structural issues such as healthcare access, education, and infrastructure.

Why Geography Matters More Than Ever

It’s tempting to view mortality data solely through the lens of personal responsibility—diet, exercise, and smoking—but the study reinforces a deeper truth: zip codes can be as predictive as genetics. Access to trauma centers, quality of air and water, and regional healthcare policies all shape outcomes long before symptoms appear.

Preventable Deaths and Local Solutions

Many of the leading causes of death are preventable. Earlier interventions, improved primary care, and regionally tailored outreach could significantly reduce mortality:

- Expanding access to preventive care in the South could lower stroke and heart disease fatalities.

- Public health campaigns in rural states could reduce accident rates through education and infrastructure improvements.

- Targeted substance abuse and liver health programs in the Southwest could address chronic liver disease.

Scott Vicknair’s analysis emphasizes that national health strategies must adapt to local realities. By focusing on region-specific risks, policymakers and communities have a better chance of reducing preventable deaths and improving quality of life across America.